I spent some time visiting with Shanghai Steve this morning. He’s one of the Minyan Regulars, showing up most Mondays and Thursdays. Since he is one of the few Levites (descendants of the tribe of Levi, the chief cooks and bottle washers in the Temple back in the day) to attend morning Minyan on those days, he tends to score the Levi

aliyah fairly often...which means he is the second to be called up to recite blessings over the Torah scroll as it is read.

I’ve written about Steve here

before. He had an interesting childhood...in the sense of the old Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times.”

He was born in Berlin in the spring of 1938, mere months before Kristallnacht, when the Nazi campaign against the Jews really began to pick up steam. His family managed to escape Germany two years later, finally ending up in Shanghai in 1940, where they remained for the next seven years.

Interestingly, the Chinese never had any issues with the local Jews. Perhaps they did not want to endanger potential future consumers of their cuisine. Even the Japanese, despite their alliance with Nazi Germany, did not single the Jews out for especial ill-treatment when they overran the city.

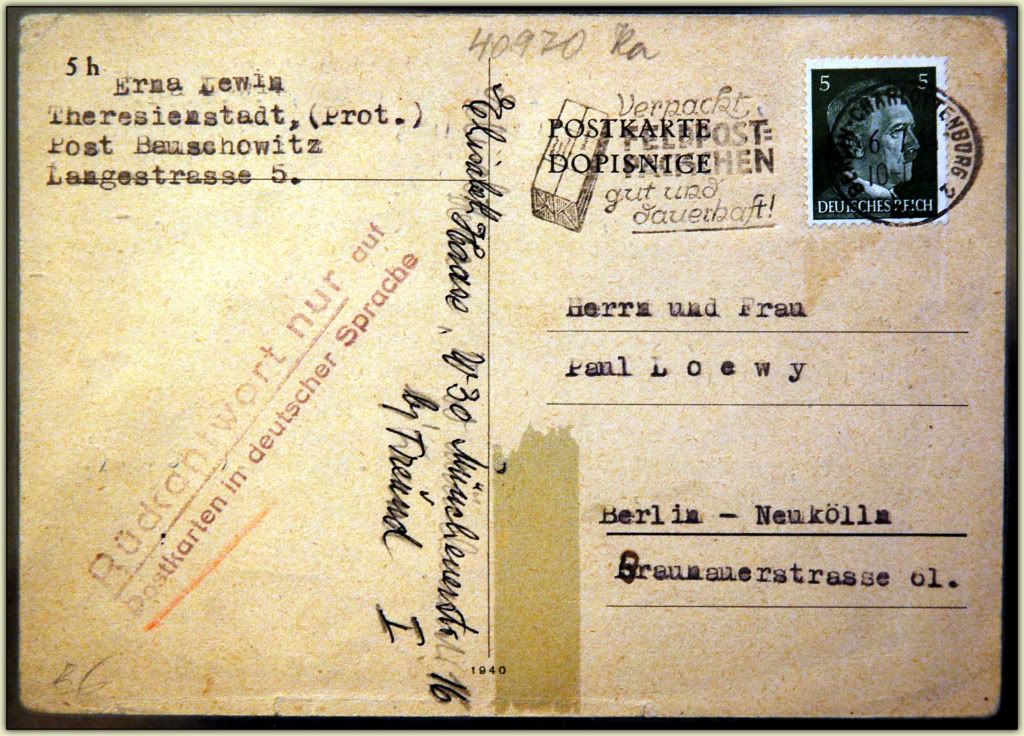

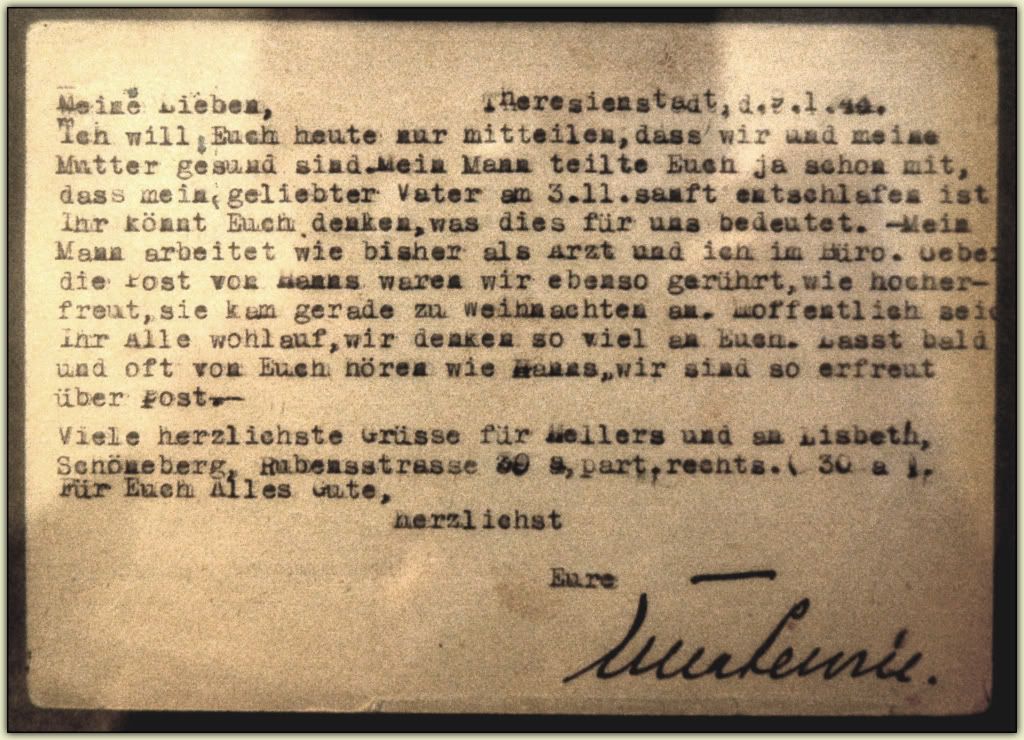

Back in Germany, however, things had become dire for any Jews who could not escape...or who had been living in areas that became subject to Nazi control. The concentration camps were up and running, and the beginnings of the Final Solution loomed.

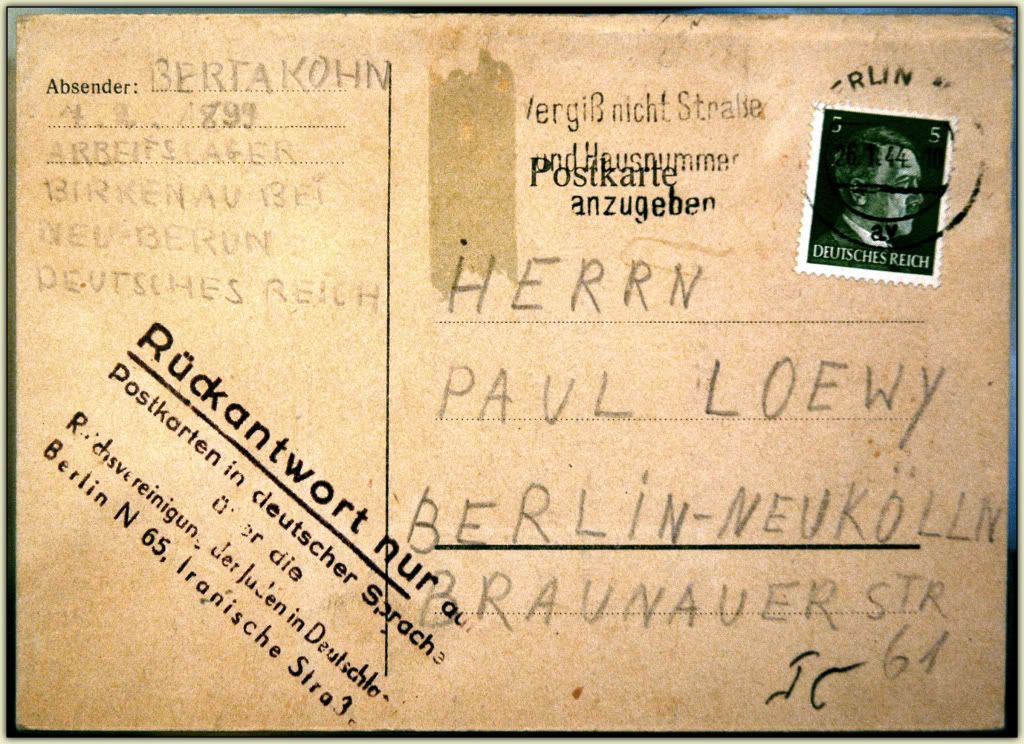

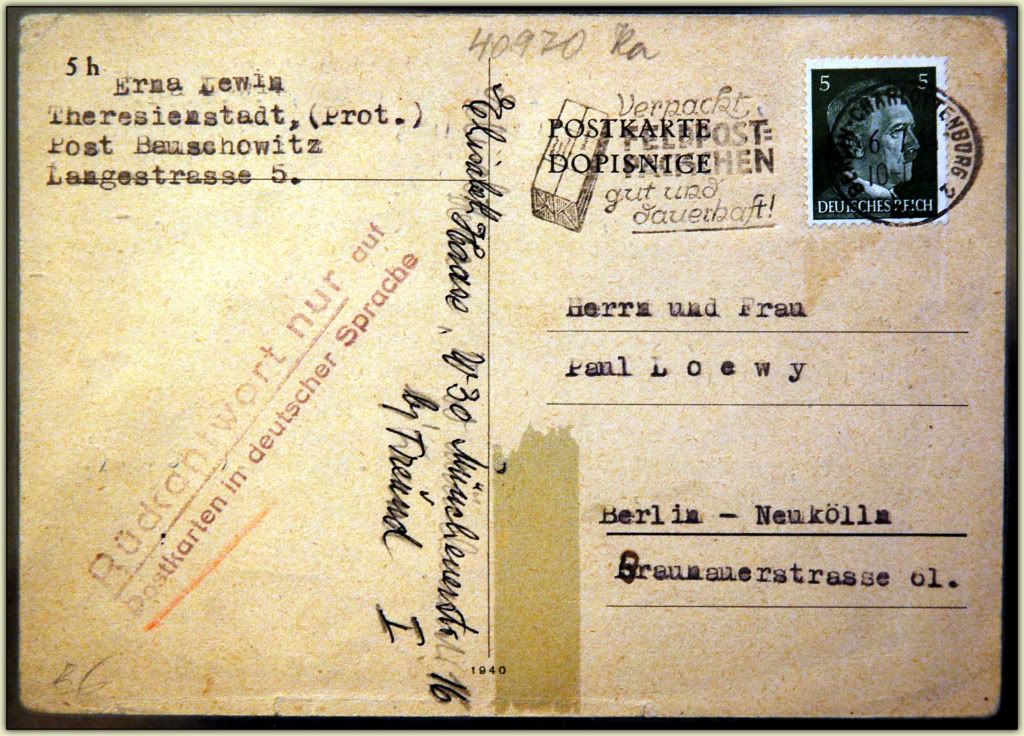

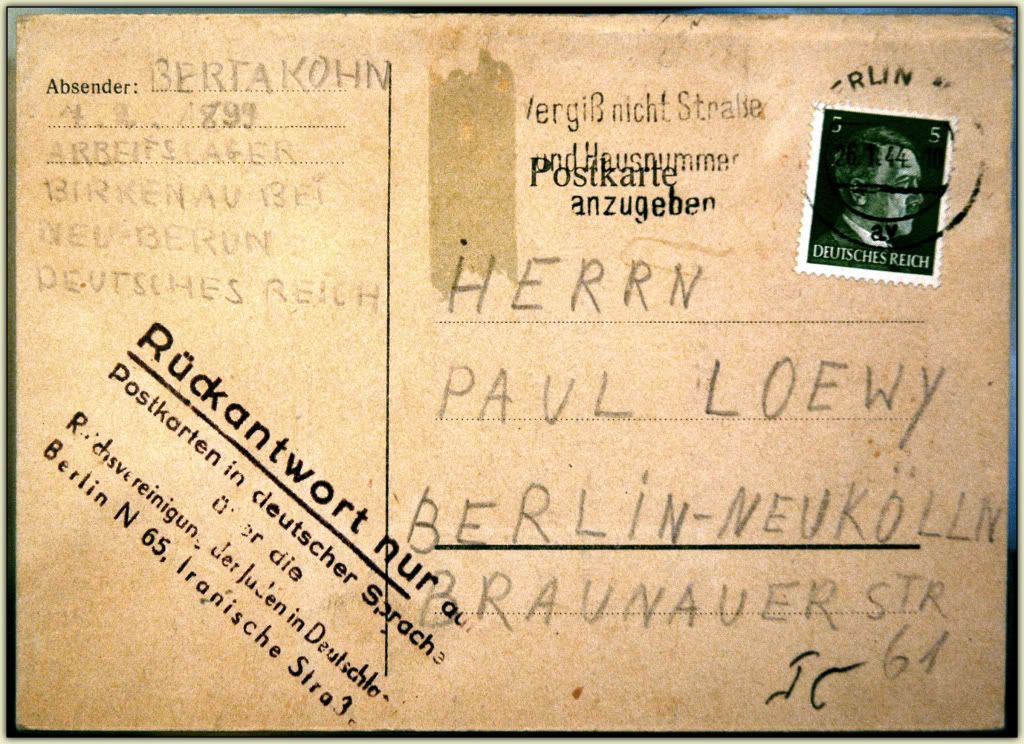

Concentration camp inmates were permitted to write postcards, at least for a while. They could even receive responses, although those responses (as well as their own cards) could only be written in German. Other languages such as Yiddish were

verboten.

[Click to embiggen.]

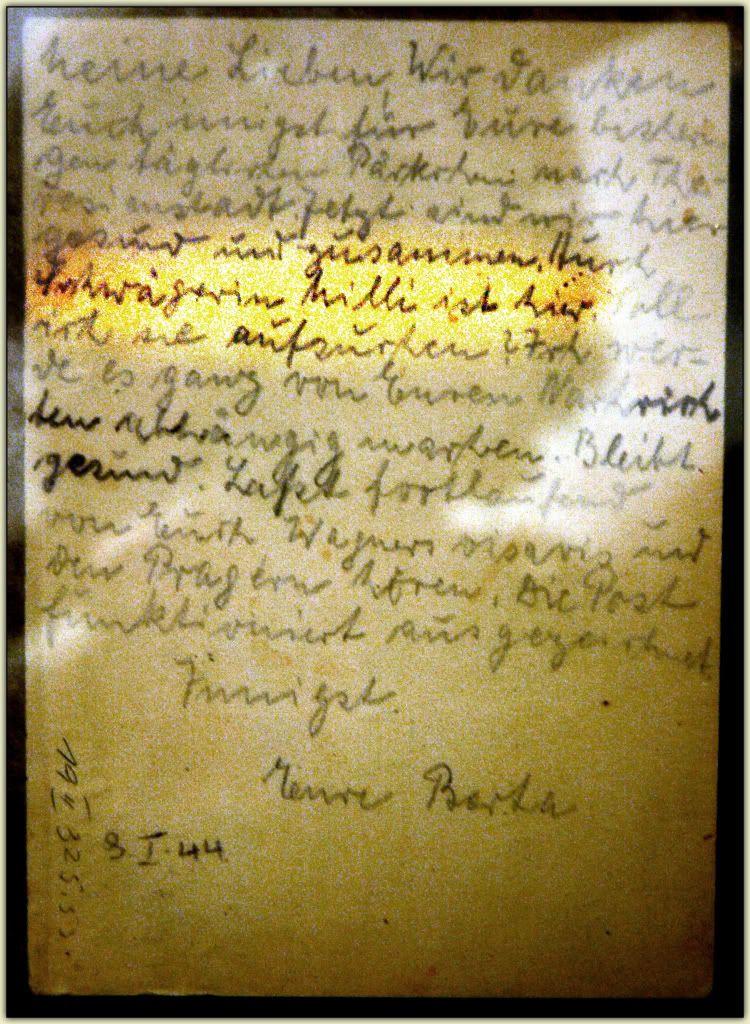

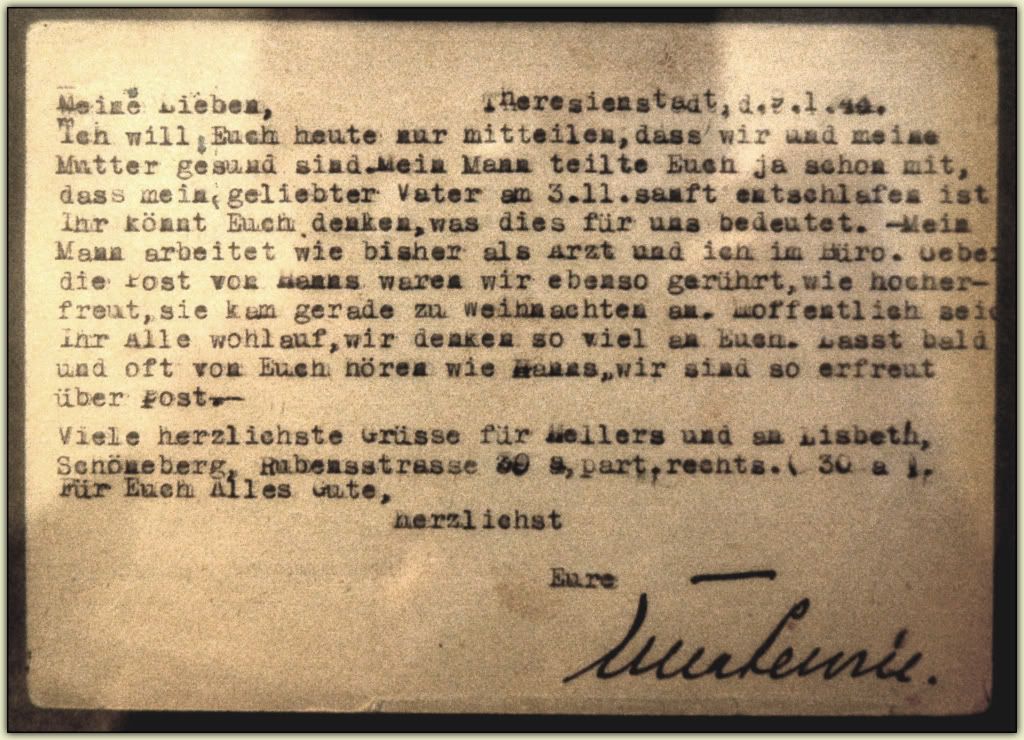

You had to be careful what you wrote, since censors went through everything with a fine-tooth comb. Even so, real information could be communicated through the use of code phrases.

[Click to embiggen.]

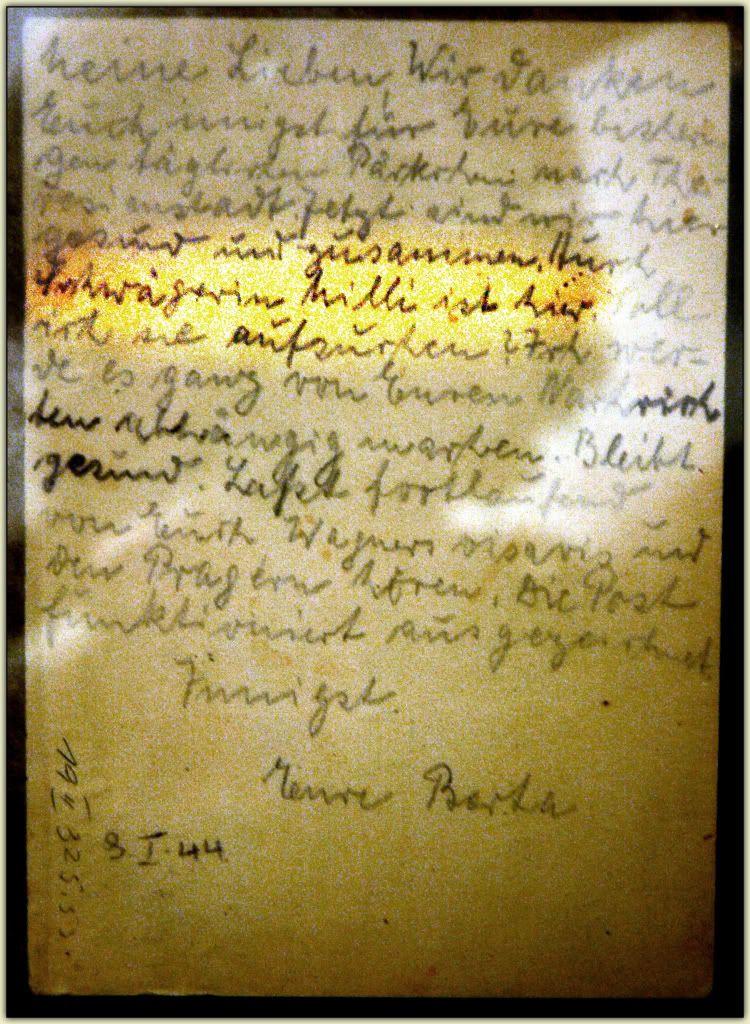

Note the highlighted words (

“Schwaigerin Milli ist hier”,

i.e., sister-in-law Milli is here). This was code that meant that someone had died.

Later, when exterminations at the camps were fully underway, the German authorities would cynically arrange to send fake postcards from deceased inmates in order to ensure that remaining relatives remained unaware of the fate that eventually awaited them.

Steve’s relatives, including the aunt and uncle who sent these cards, perished in the camps. But he was safe, half a world away.

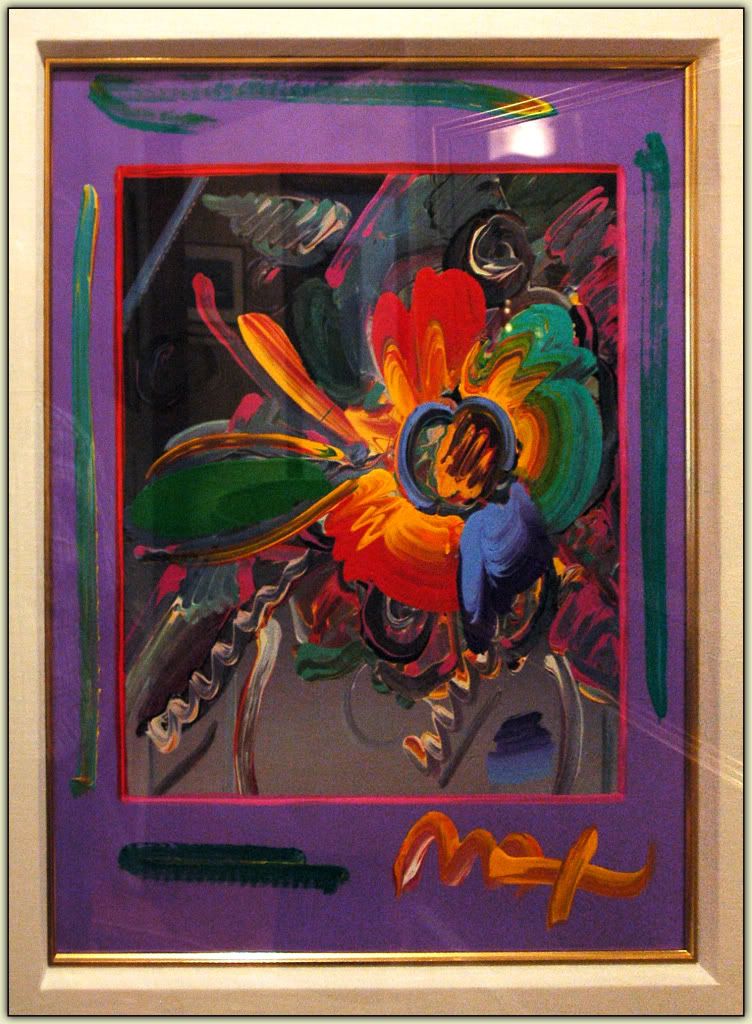

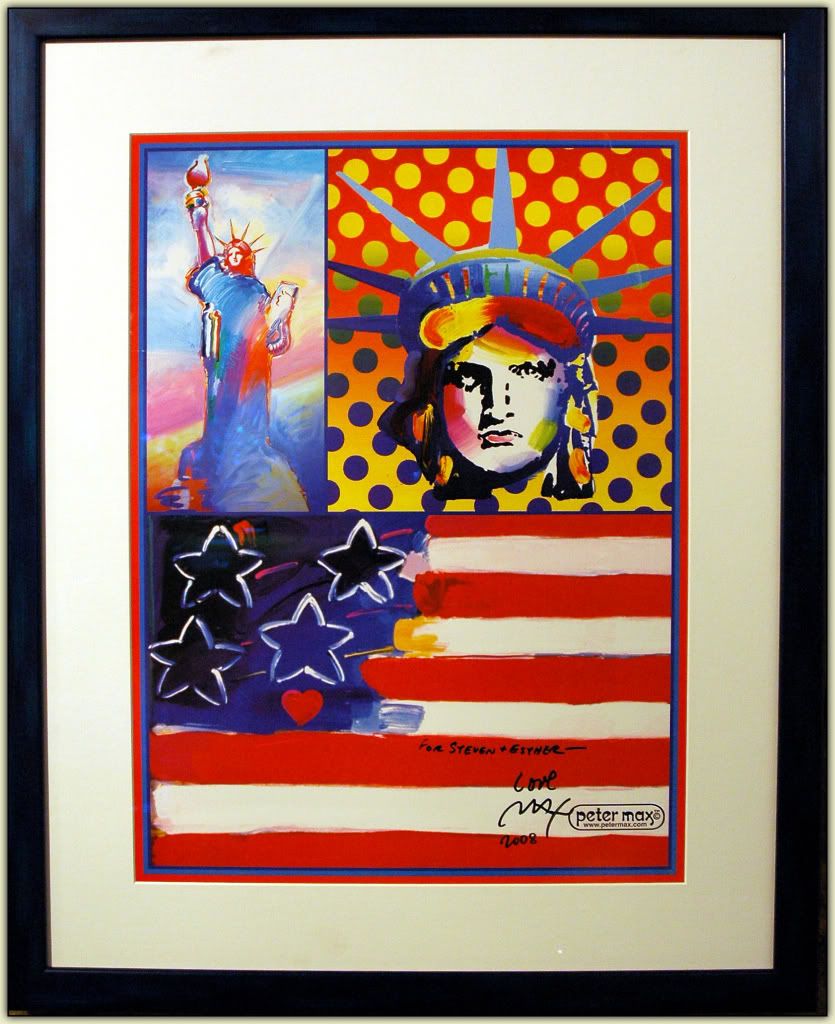

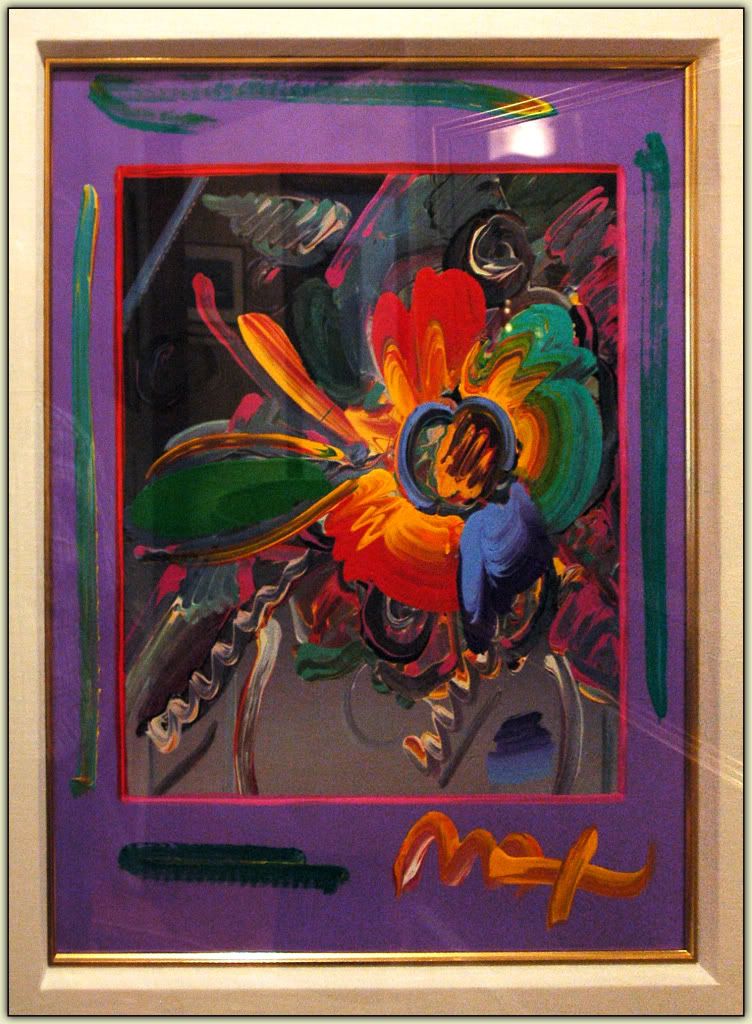

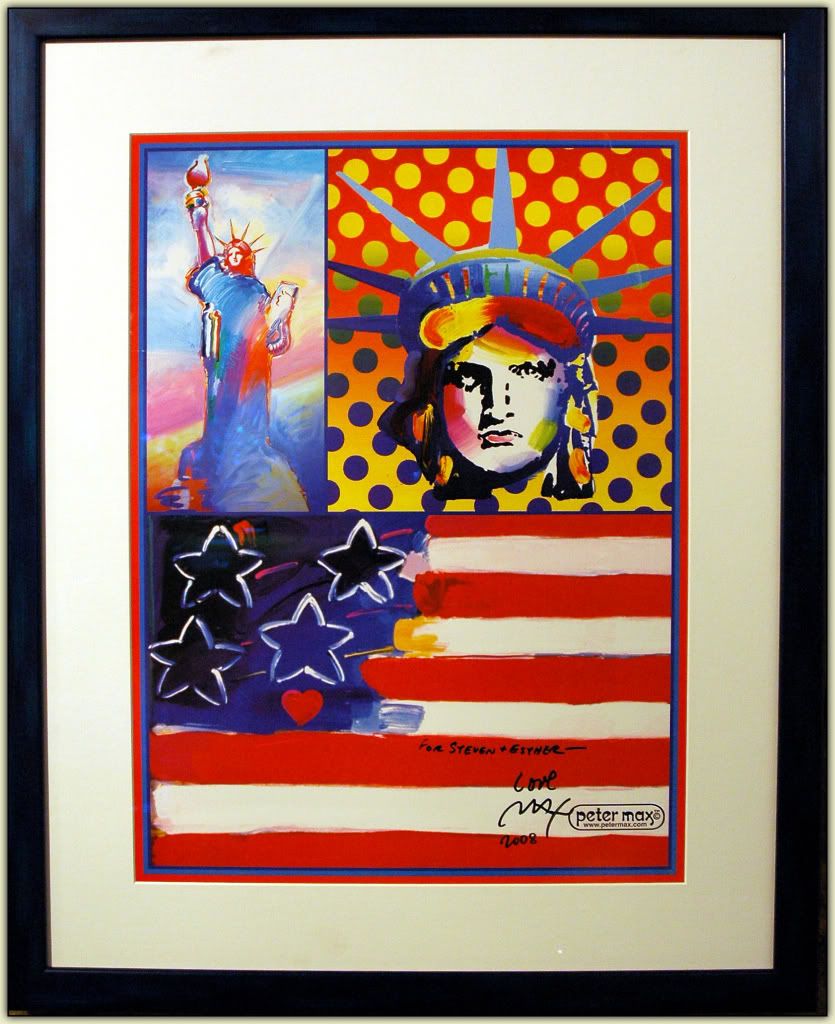

Among the Jewish refugees there in Shanghai was a boy who would later grow up to be the artist who, more than any other, would define the visual backdrop of the late 1960’s: Peter Max. Steve has several Peter Max originals - oils and prints - hanging in his home, including at least one with a personal inscription.

Whenever Peter comes to town, Steve makes it a point to visit his old friend and neighbor...and he always gets a warm greeting.

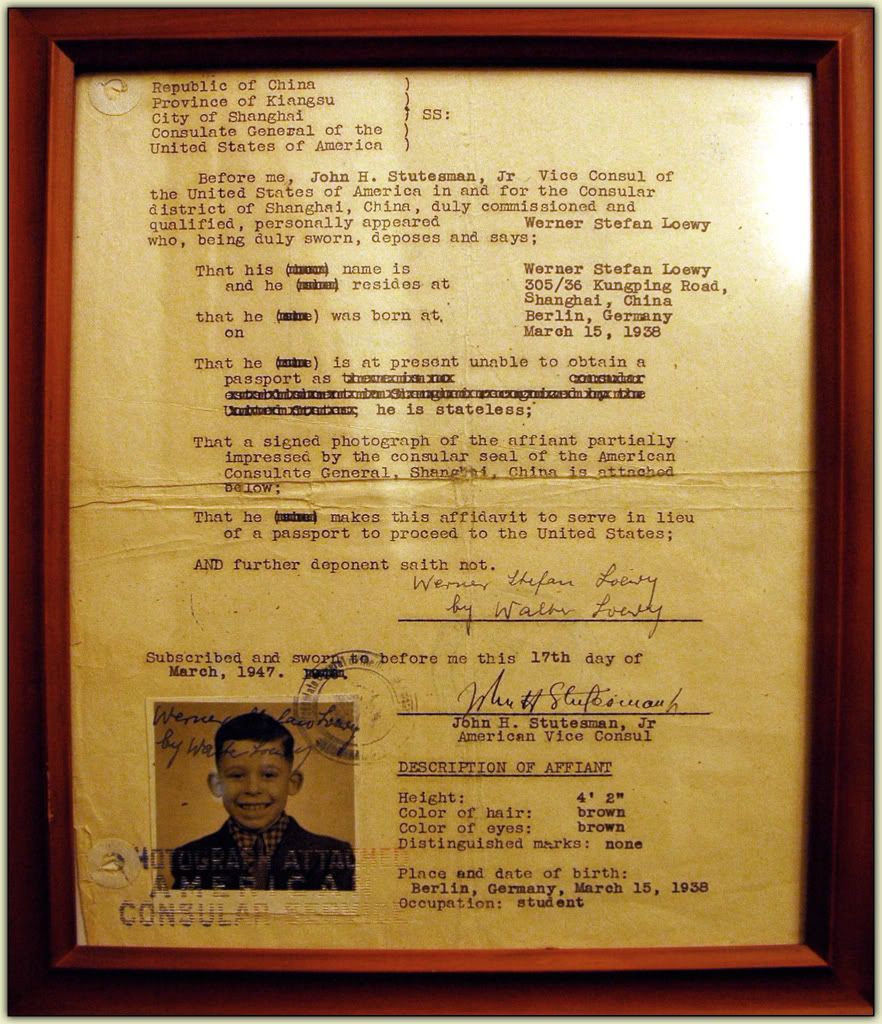

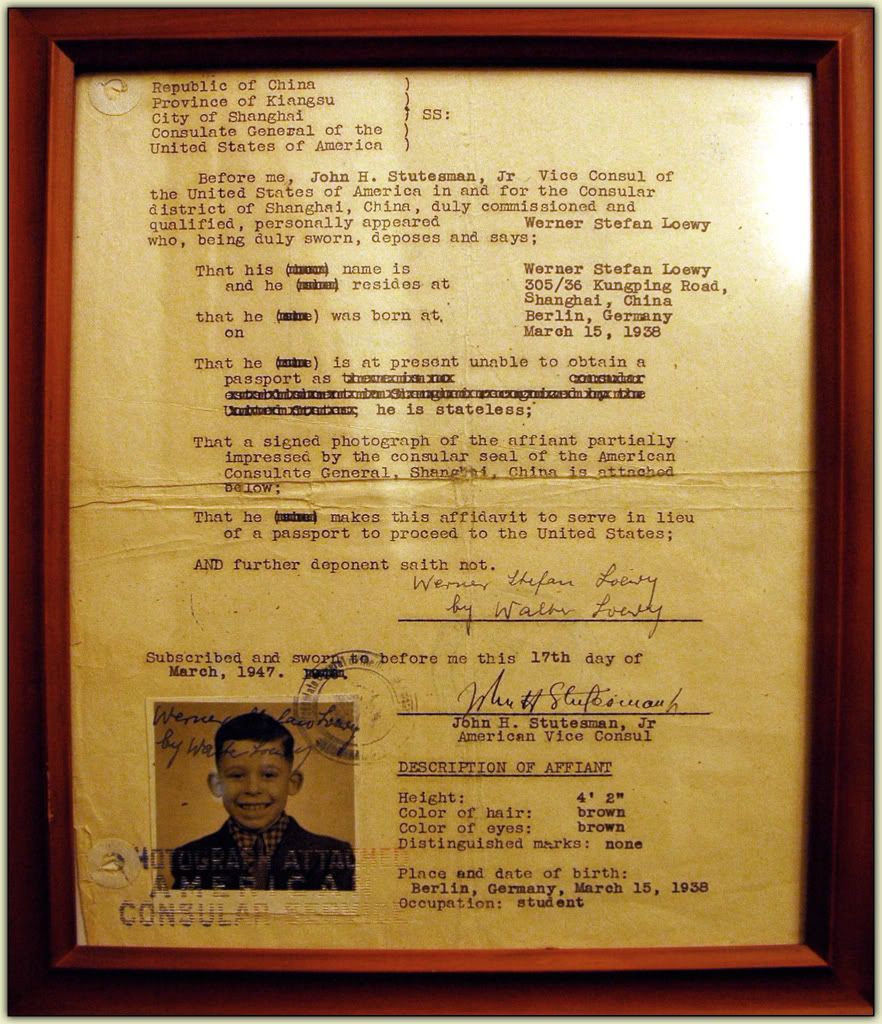

In 1947, the family left China and emigrated to America. As refugees from the Nazi horror, they were stateless. Here is the affidavit that Werner Stefan Loewy (his original name before becoming “Shanghai Steve”) used in lieu of a passport to gain entry to the United States:

“AND further deponent saith not.” [Click to embiggen.]

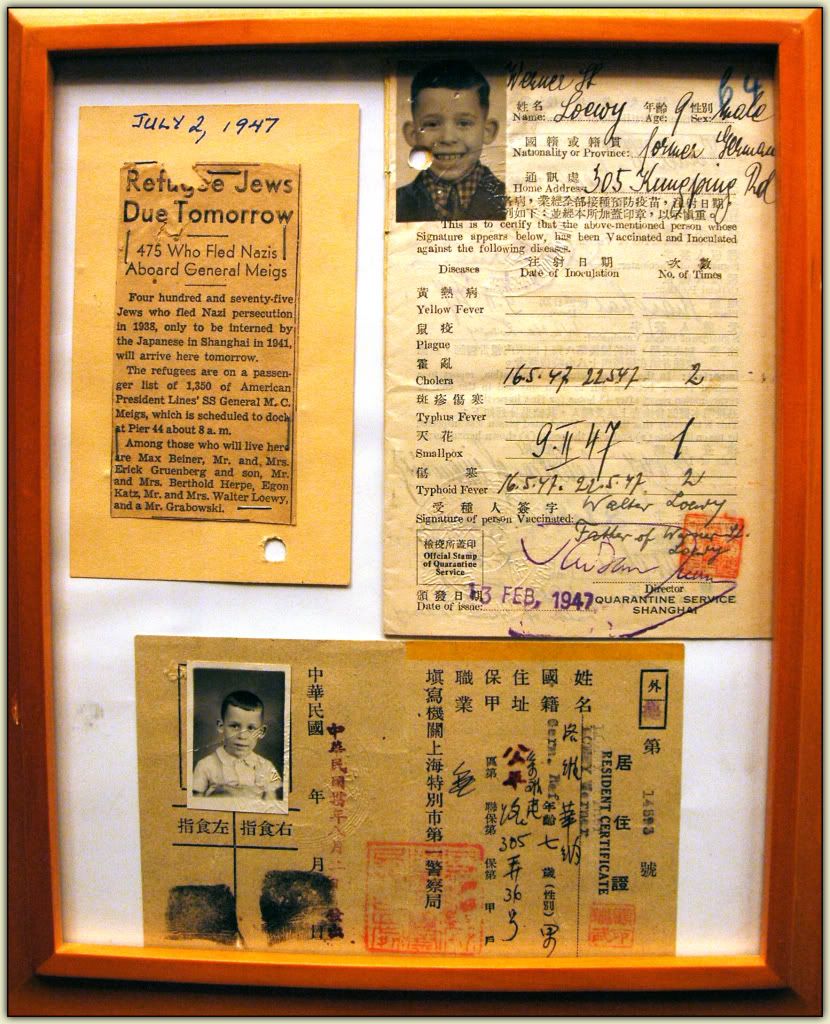

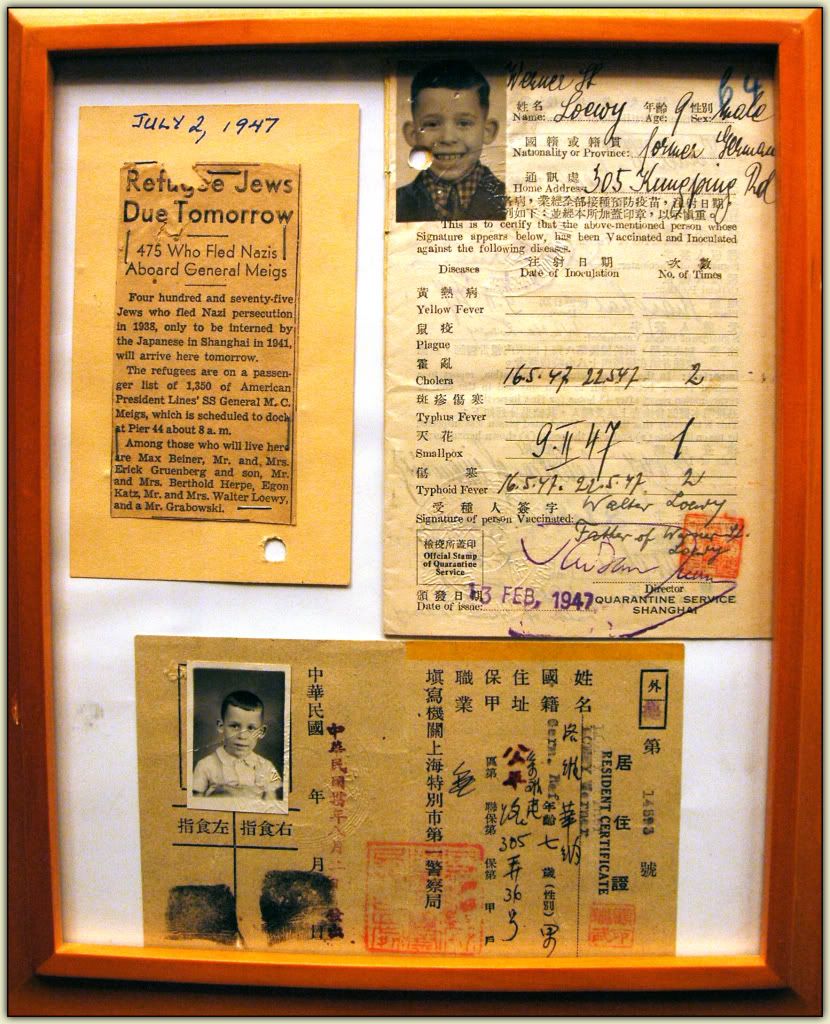

More travel papers, as well as a news article about the soon-to-be-arriving refugees:

[Click to embiggen.]

All of these documents were carefully kept by Steve’s parents, who must have had some idea that they would be valuable one day...or at least of passing interest to their son. But now they tell a story of fear, flight, and ultimate redemption that is beyond the reach of a price tag.

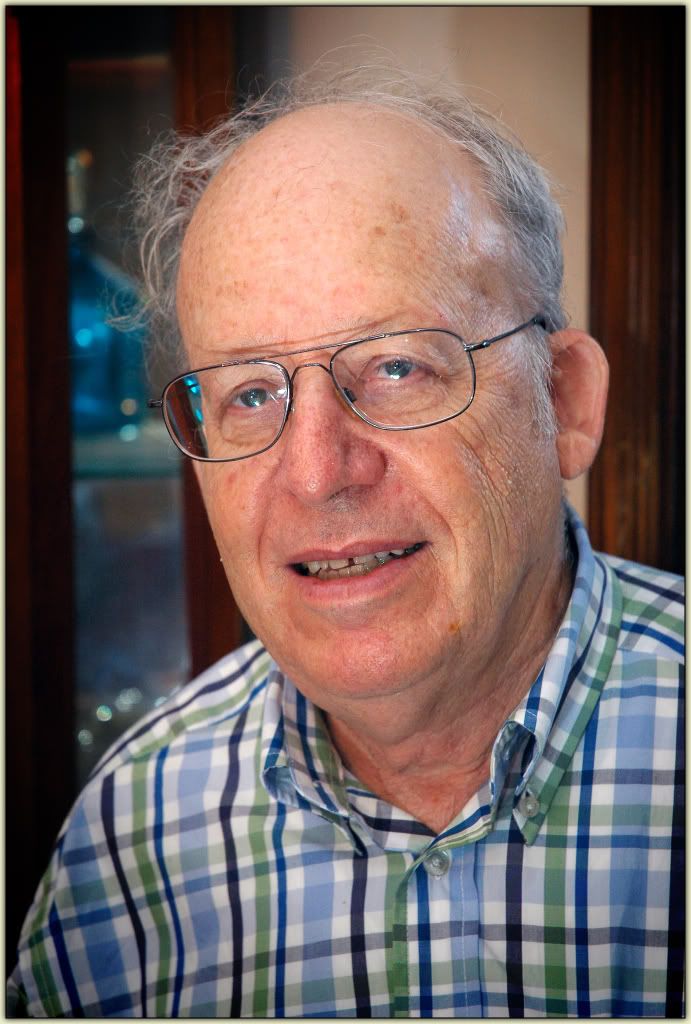

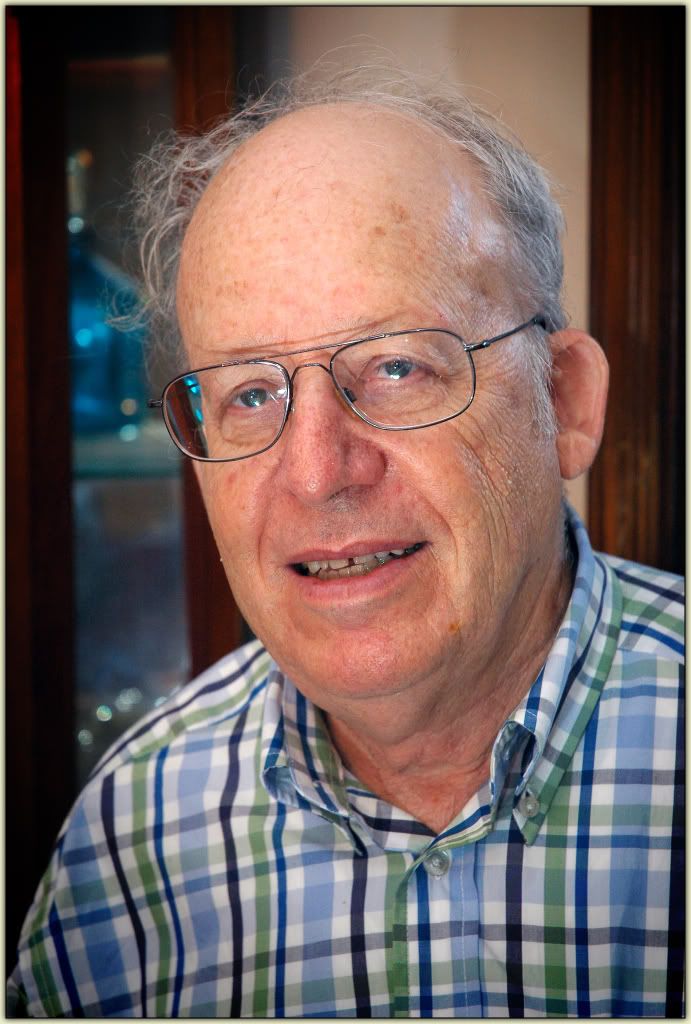

Steve has grown a little older since his travel documents were prepared 61 years ago, but he still has a ready smile and a Harry Potteresque twinkle in his eye. Because, like Harry Potter, Steve is the boy who survived.

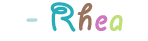

Shanghai Steve today.